Ashton Applewhite is an author, blogger, speaker and anti-ageism activist. After publishing a collection of humorous books and other works, Ashton turned her attention to the ageing process and the idea that what is commonly accepted about later life might be wrong. The resulting book, This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism has become one resource of many that she’s created to help educate and arm people in the fight against ageism.

As she says in this interview “[I] realised in a matter of months, if not weeks, that everything I thought I knew about late life was way off base, way too negative, not nuanced enough or flat out wrong.”

Ashton shares with Ash how big a problem ageism is (particularly within aged care settings), and how it affects everybody regardless of their age. She also provides some guidance for people who are witnessing ageism and aren’t sure how to make other’s aware of their biases. This episode is a great compliment to the interviews with Emi Kiyota and Laurie Buys, and it highlights that older adults can still be valuable members of the community.

Transcript

Ash de Neef: All right, Ashton, thank you so much for joining us on the program today.

Ashton Applewhite: My pleasure.

Ash de Neef: Can we start with a little bit about you, your background and how you came to be doing the work that you’re doing now?

Ashton Applewhite: My heart always sinks when someone wants my resume, because nothing about my resume would give a clue as to what I’m doing. As I could never figure out what to be when I grew up or barely even what major in, university. And I realised in hindsight, as I realised everything that the reason ageing is so fascinating is because there’s no, topic, no domain, no philosophy, no area of economics, you name it, to which ageing is irrelevant. It is how we move through life.

Although I must say that if you had told me 10 years ago that I would be fascinated by ageing, I would have said, “Ooh, why do I want to think about something so sad and depressing?”, when it is in fact anything but.

And I am a self-employed writer and I started thinking, about getting older when I hit my mid fifties, I’m 68 now and realised I was really apprehensive about it. So being a think-y sort of person, although I’m not an academic, I started researching longevity and interviewing people over 80. And realised in a matter of months, if not weeks, That everything I thought I knew about late life was way off base, way too negative, not nuanced enough or flat out wrong.

And that was really the catalyst for what turned into a blog, and then another blog, And then I realised I had to write another damn book about questioning, why our impressions of late life are so negative when the evidence all around us is that it is a far richer And more nuanced process.

Ash de Neef: Yeah, fantastic. And I think that really touches on that it’s hidden in everything that we see around us and the way that people talk naturally. Can we just spell it out very clearly? What is age-ism and what is it specifically that we’re talking about when we talk about ageism?

Ashton Applewhite: The dictionary definition is discrimination and stereotyping on the basis of age.

We are being ageist anytime we make an assumption about someone or a group of people on the basis of how old we think they are. We live in a hyper capitalist youth obsessed society, so most of the bias and the brunt of age-ism is born by older people. But again, it is any judgment on the basis of age and younger people experience a lot of it too.

Anytime you look at a young person and you think, “what could you possibly know, or how could you be old enough to have enough experience to be good at this thing?”, you’re being in that situation as well.

Ash de Neef: Great, that sounds good to me as well. I remember some situations with former employers have been making generalisations about millennials and that always got my goat.

Ashton Applewhite: Oh, it’s so annoying, right? I mean, The assumption that, what my favourite or least favourite trope is that, millennials aren’t loyal on the job. I think y’all are getting old enough now that’s no longer the case. You’re no longer trying to get established in the job market.

But I like to point out that when people, my age were that age, we change jobs all the times too. Because we were busy trying to figure out our career path in life. It’s not an age effect. It’s not a function of being of a given generation, it’s a function of being at that stage in your life.

And it’s a completely unfair stereotype, but how could any generalisation about all people between ages X and Y possibly be accurate?

Ash de Neef: What is this? Because we’re othering people here, right? Why are we doing that?

Ashton Applewhite: The weird thing about ageism in the sense of discrimination against older people is that the other right, all prejudice relies on seeing a group of people as other than ourselves, as you mentioned. You know, other religion, other nationality, other sports team. In agesim the other is your own future older self, which is nutty, if you stop and think about it.

Where does that come from? That’s you know, a question that touches on biology on philosophy on sociology. I do think there is something tribal in human nature a little bit, if the barbarians are at the gate, we do tend to group with people who look like us who have shared experiences. Because your lizard brain says they’re more likely to take me in to not be dangerous.

We have evolved a long way from lizard brains and barbarians at the gate. And I think everything we have learned as, especially in a multicultural globalised world, that those primitive, that’s probably a problematic word to use, but those primitive instincts do not call on our higher selves.

And foster divisiveness and God knows in a world as complicated and facing as many conflicts and challenges as we are as human beings, we need to find common ground and joined forces against the really scary stuff that we’re up against. Like in my opinion, climate change and inequality in the broader sense.

Ash de Neef: Hmm. And you’re making sort of a career at the moment out of calling out age-ism in doing this in lots of forums…

Ashton Applewhite: And what a career I’m making buckets money. Go for it, join me.

Ash de Neef: Haha! Everybody should come to this line of work, but how do you do that? Because it’s not easy. It feels like when I think about the situations in which I’d need to do that, it’s very awkward, right?

Ashton Applewhite: I mean, I guess what I do in that sense is social justice activism.

And of course there are many thousands of people doing activism around climate justice, indigenous rights, you name it. You’re right that it is not easy work because it involves culture change and it is really hard to unlearn things that we believe. That we absorb largely unconsciously in an ageist, sexist, racist, you name-it-ist culture.

None of us are free of bias and most of those beliefs are unconscious and we can’t challenged those beliefs, unless we become aware of them. On the other hand, when it comes to age-ism the most daunting thing about it is also the most fun in that it is relatively unexamined.

So people who read my book or listen to me talk, they’re like, “oh, gee whiz”, they smack their foreheads, “I never thought of that”. It’s not that I’m such a genius it’s that I got here first or first-ish, relative to other people.

It’s like cleaning a really dirty window, you can see where you’ve been, which is gratifying. And I also feel one of the things that I find uplifting or positive that keeps me going is the fact that if you compare where, I don’t want to speak about all cultures, but progressive thoughts thinking worldwide is. 50 years ago to say that a woman could run a company as well as a man, or that for that matter that a man could care for children, as well as a woman. These were radical ideas, right?

And now the ground has been plowed. So many of my predecessors and contemporaries have been doing and continue to do such a remarkable work around our awareness of homophobia, of transphobia, of racism, of sexism, of gender bias. You name it.

That to say to people, “gee where’s age?”, a lot of times people don’t add age to that list. They don’t think of age, for example, as a criteria for diversity. But when I say, “how about age?”, no one says that’s a dumb idea. No one says, “let me get back to ya.” They say, “gee, you’re right.”

So I think I am building on a momentum that is a cultural readiness for these ideas that was not the case decades ago. And so I’m, very optimistic about the rate of change. I mean, a global movement to end ageism is underway.

Want to know why I’m not tripping when I say that?

Ash de Neef: Yeah, go for it.

Ashton Applewhite: You should know as an Australian, as you probably do, that to my knowledge Australia launched the very first national anti-ageism campaign. Which brought me to Australia for a fantastic, amazing tour of the country in November, 2019.

And it’s called Every Age Counts. And at the time I had just launched with two co-conspirators a website called Old School, The Old School Anti Ageism Clearing House, on the theory, it was just a theory, that movements need tools and best practices and ways to share them. And since this movement was really new, wouldn’t it be fantastic to have really good stuff all in one place where people could find it. And at that time we didn’t even have a campaigns section, and it is now three years later, one of our fastest growing sections. So that is data, that is evidence.

And these are not organisations promoting how to live forever or how to not be lonely or how to be healthy. These are political and economic campaigns to raise awareness of ageism and how to dismantle it. Every Age Counts is one of my favourite, but it’s also really exciting to let you know that the World Health Organisation launched a global campaign to combat ageism.

And that’s not my wishful name for it, It’s the World Health Organisation’s Global Campaign to Combat Ageism, this March. And that’s not the world old people organisation. That’s the world health organisation, which has been a little busy this last year with a global pandemic, by the way. And yet they launched this campaign to acknowledge that the biggest barrier globally to making the most of longer lives, the longer lives that are a global permanent demographic phenomenon, is ageism.

Ash de Neef: Well, This is fantastic progress then, right? To think about how far things have come in the time that you’ve been doing this work.

Ashton Applewhite: Yeah it really is.

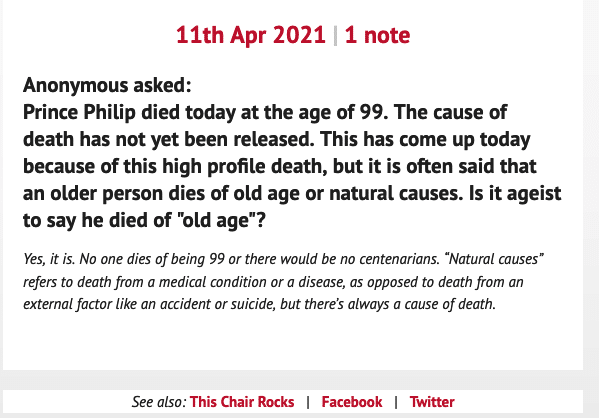

Ash de Neef: And you’ve got the, “yo is this ageist?” blog. Which is based on the model set up by the “yo, Is this racist?” blog. But can you tell us some of the uh, how does the format work and what are you doing there?

Ashton Applewhite: Oh, sure. Yeah, I’m a huge fan of “yo is this racist”, which a guy set up years ago on the theory that, which is pretty clearly the case, that we are awkward talking about race. And so you can write in a question and he answers it, his answer is usually hell yes, that’s racist.

So I set up, “yo is this ageist” in frank imitation, but I did obtain his permission, on the theory that we don’t know that much about age-ism. And that it is helpful to have an arbiter say, you know, if you hear or do perhaps, or encounter something that you wonder whether or not it is ageist, send it into me. It can be a photograph, it can be something you heard on the radio, it can be something you did, it could be a job listing. And I weigh in on whether or not it’s ageist.

And I mean it’s actually quite hard to do because a lot of the questions have to do with ethics, which are never easy to write about. And also all of these things are you know, changing, culture is immutable, it’s not that these value systems are fixed.

But a really good rule of thumb is that if a similar comment let’s say, or image on the basis of race or sex would not pass muster, then it’s not okay on the basis of age either. Even though it may seem less offensive to us because we are less aware of why. It’s no more okay to mock people on the basis of age, or belittle them or dehumanise them, then it is on the basis of any other characteristic about ourselves that we cannot change.

Ash de Neef: Yeah. And there was a really good example on there that I was trawling through some of the submissions in your responses. And there’s one about –

Ashton Applewhite: Which are hilarious, and original and fun to read.

Ash de Neef: Haha yes, exactly. There was one really interesting one that really stuck out to me about Prince Phillip, that when he passed away, there was no publicised cause of death. And someone was asking, “is it ageist to suggest that he died of old age at 99?” And maybe you can give us the explanation of why it might be ageist?

Ashton Applewhite: It is. And I consulted with physicians, you know, there is always a cause of death. I mean, there are two, only two, but there are two inevitable, bad things about getting older people. People you’ve known all your life are going to die, which is awful. And some part of your body’s going to fall apart.

Cognitive decline is not inevitable, but your body does not work as well as it used to. And the older we are, think of an old car, right? The better the odds that the windows might not work. And then the carburetor might go right?

The longer you live, the shorter your future lifespan is likely to be – that is real. But to say someone died of old age, is ageist. He died of heart failure or something, he died of complications of XYZ. But people don’t die of old age.

One of the reasons people use to justify ageism, which riles me because no prejudice is acceptable either. We shouldn’t try and wish them away is, “oh, gee, you know, old people are going to die anyway,” old people. So age-ism is “natural”. Watch out for that word.

Because of that fact, there’s always a grain of truth just as there is in the fact that, older bodies are more vulnerable. And it’s true that older people are reminders of mortality. There is more road behind me than ahead. That’s for sure. You are way more likely to live longer than I am.

But you might look at me, you plural, and think I’m ancient, but you don’t look at me and think I’m dying. Dying is what happens at the end of all this living. Ageing is living. It is not something annoying that old people do. We are ageing from the minute we’re born.

So one of my many pet peeves is when older people are described as ageing, ageing, parents, ageing celebrities. Three-year-olds are ageing, everyone’s ageing.

The adjective in that context is older. And Prince Philip died of something when he was really damn old, which did have to do with the fact that he is not still kicking. But it’s not the reason he’s not still kicking today.

Ash de Neef: Yeah. Thank you. It’s a good clarification to make. And I think for a lot of our listeners who work within the aged care industry, they’re going to hear attitudes and words especially things like elderspeak, which you’ve spoken about before. Can you maybe touch on what is elderspeak and how can that be detrimental?

Ashton Applewhite: Sure. Elderspeak I believe is a term coined by Becca Levy, a fantastic public health and psychology scholar, at Yale University. To describe the awful habit of describing older people as “hun”, or “sweetie”, or “dearie”. and condescending to older people.

And studies show that even people in advanced dementia, who have advanced dementia when they are spoken to in this way, get agitated. Nobody likes to be condescended to. Three-year-olds don’t like it and a hundred and three-year-olds don’t like it. And it is demeaning.

And someone wrote in to “yo is this ageist?”, “is it okay to call an older person, sweetheart?” And every so often I come up with a snappy answer and I said, “yes, if they’re your sweetheart.”

But otherwise a really good rule of thumb, especially in the minefield of what is politically correct, what do we call people whose gender might be not clear to you, et cetera. Really simple – ask them.

And think, if that’s not possible, think how you might want to be treated. Think how you think they might want to be treated. If you don’t want some stranger to call you dearie, then don’t do it to some stranger yourself.

Ash de Neef: Yeah, absolutely. But you also need individual people to start changing and to start calling out things that they see to be inappropriate or ageist. How can people start doing that in a way that’s not extremely confrontational?

Ashton Applewhite: Yeah, that’s a great question. It’s a great question, and it’s hard. It does take courage and you’re absolutely right that we need, the big companies to orchestrate change but all change starts within, as the saying goes.

And if we ourselves, the first step is to become aware of our own bias, which is never fun. Whether it’s, racism or sexism or – and we’re all biased. The good news is that the minute you start to see it in yourself, and my favourite comment about my book is like, “oh crap, I had no idea how many of these ideas I had absorbed and degree to which I’m part of perpetuating bias.”

The very next step though, and it happens automatically is that you start to see it in the world around you. You start to see it in advertising. You start to see it in that wretched birthday card aisle. You start to see the absence of older people in advertising, for example. And then you realise, “oh, it’s not that I’m a bad person. It’s not that I have failed here. It’s that I live in a culture that’s saturated with these messages.”

How to push back? Take a deep breath and you never want to get someone in a gotcha moment, because when we put people on the defensive, as I think you already know, then they just dig in. They’re like, “you have no sense of humour”, or, “you don’t understand what I meant”. It is hard to criticise and it is hard to be criticised.

But a really good all purpose rejoinder is “what do you mean by that?” For example, “aren’t you retired?”, “what do you mean by that?”

You could say, “why would you ask?”, but that’s even more pointed. So just, or, “tell me about that? Let’s talk about that, what’s behind that question?” And try and open the way to a discussion about it.

But I urge people and it does take courage, but that is how we change the culture. If everyone just goes along with that, it’s the same as if we see someone being harassed on the street. Or are in a meeting where someone without a whole lot of privilege is shut down or isn’t getting called on. Say, “hey Louise anything to say about that?”, or, “I notice we haven’t called on Phil since we…” I mean those are lame examples, but – oh, and you shouldn’t say lame, that’s a hard habit to break, because that’s abelist.

We’re all learning. You make a mistake like that you say, “you know what? I shouldn’t have said that” – I learned that in a very gentle way. In one of my talks, I used to set talk about my darkest fear, and this will resonate with some of your listeners who work in what in Australia you call aged care.

I used to say my darkest fear about getting older was ending up drooling in some grim institutional hallway. And my niece called me and she said, “auntie,” she’s a physician, and she said, a” lot of my patients. And they really don’t like it and they’re embarrassed by it. And I wish you wouldn’t say that anymore.” And I don’t say that anymore.

But she called me out in a really gentle way. And did my face flush? My face flushes now, five years later because no one wants to do those things. But I am so grateful truthfully, that she called me. And I have other friends, I’m better on age-ism and ableism than I am on my class and race privilege.

But when someone says, “you might want to think about what you said”, I do flush. But I am grateful that they’re giving me the opportunity to learn. I hope that doesn’t sound like Ms. Goody two-shoes,

Ash de Neef: As, you said, it’s, as we’re shifting our attitudes and we’re trying to make a change in the way that we treat other people, we are going to miss step and we need to be open to having mis-stepped and being politely and kindly reminded that we should have another look.

Ashton Applewhite: Yeah be gentle. Another thing, I just learned that lame is not ok to say, and it’s a habit and I’m trying to break it.

Ash de Neef: Yeah. And it’s a process. It’s not…

Ashton Applewhite: It’s a process and I’m in the same damn boat paddling, maybe sometimes in the right direction and sometimes not so much.

What you want to do is encourage that moment of reflection. The only really good snappy answer I’ve come up with in all these years is when someone says “you look great for your age”, say, “you look great for your age too”.

Ash de Neef: Yeah.

Ashton Applewhite: And let that uncomfortable moment sit there. That’s the hard part is not to rush in and fill that uncomfortable void, because it someone has to think about why something they intended as a compliment doesn’t feel like a compliment.

And I just want to remind everyone about the old school clearing house. The website is old school.info because we have tons of resources about language. Search for language, and a number of them are created by and for people who work in ageing services, as we call it in the US. And have tools for ways to educate people who live in congregate settings, people who work in them to change our language in a way that’s more, more equitable and more sensitive.

Ash de Neef: Yeah. Fantastic. I can see that it might be difficult when they’re responding to a lot of needs of the people. And it’s difficult to see them as fully complete adults who have their own lives, who don’t necessarily need to be spoken to like that.

Ashton Applewhite: No. And especially if they are really incapacitated. I mean one of the things that was a surprise to me, but remember I came into this knowing nothing with no degree in gerontology, no expertise in aged care. Is that people in ageing services can be very ageist.

And I think one reason is that they do the incredibly important and undervalued, especially here in the US, work of caring for people at the most debilitated end of the spectrum. So that’s the people they’re exposed to and that is where their expertise lies and their professional identities and even their funding.

I also think it is a really hard job, and I am not condescending for an instant just the opposite, to reconcile that view of late life with what we hope lies ahead for ourselves. Age-ism takes root in denial, in not wanting to think about, in that othering, your own future older self.

That’s never going to happen to me. Don’t call me old. I’m in some like permanently youthful category, I’m joking about that. But, you know, I don’t want to think about it because it’s scary.

And because I haven’t reconciled that view with what I hope lies ahead for myself, and that’s a huge, hard job. It’s a hard job for anyone, and it’s a really hard job if you are surrounded by people who are incapacitated. Who never the less are living lives of value and deserve to be recognised in their full humanity, as you just said.

Ash de Neef: Absolutely. And uh, as you’re speaking there, I was reminded of something that I caught myself thinking the other

Ashton Applewhite: There you go!

Ash de Neef: When you see, yeah, You see, a picture of somebody from the seventies or eighties when they’re a bit younger and then you see them next to a picture of them now. And you’re like, “oh look how the, their face has changed over time.”

And I have this kind of feeling of their real face or their default face is actually the younger one. And that their faces is changing in some way to adjust to time when there is no natural or default face. It’s just everybody changes.

Ashton Applewhite: There are lots of old things that we think are beautiful, old furniture, there’s this Japanese idea of wabi-sabi where things crack and they fill the cracks in with gold and celebrate the “imperfections”, which according to their aesthetic, make it more beautiful. So just think of these wrinkles, feel free to fill them with gold. They are the map of my life and I’m not ashamed of them.

Do I have moments when I look in the mirror in the morning and go, “Hey, what happened?” Sure, I’m human. But I have fewer of them than I used to.

And it’s important to beat back these messages of that appearing to age is somehow catastrophic or a failure. Bob Dylan just turned 80 and a lot of the pictures of him were of his much younger self. There were very few images of him as an old man, and that’s a problem.

Ash de Neef: I guess there’s this feeling that people would just want to see the younger youthful bob Dylan.

Ashton Applewhite: But when we hide people away, no matter what, it’s a problem. And there’s a fancy term for it in media studies called symbolic annihilation, which is the lack of representation. And if you just, I am now much more attuned, I notice when I walk in the room or watching a TV show or something, I notice when everyone’s white.

I think we’re not yet attuned to noticing when everyone is young, or, you know, a billboard, campaigns, advertising. And when older people are represented, there’s all sorts of studies about it in the movies, that older people are vastly underrepresented. And when we do show up, we tend to be portrayed as impaired.

It’s really important to represent disability. It’s really important to have wheelchairs and walkers. Our bodies fall apart, and not to just show the older people who are ageing, who are exceptionally fit and active. We need to show the full spectrum, but we need to show people all together in all our diversity.

If there’s one fact I would love to Telegraph to every brain in the world. It is that the longer we live, the more different from one another we become .

We have this crazy idea that, you wake up old one day and then everything goes to shit and no one can think or walk or move or have any fun.

And in fact, if you think about it, every newborn is unique, but 17 year olds, have a lot more in common developmentally, physically, socially than 37 year olds who are way more homogenous than 57 year olds. And so on. So the older the person the less their chronological age tells you about them.

Any stereotype is wrong and misguided, but they are ever more ill informed the older the person you’re applying them to.

Ash de Neef: Wow. Yeah. That’s the complete opposite of the way. that we talk about older people.

Ashton Applewhite: Right?

Ash de Neef: Yeah. Ashton this has been great. And I couldn’t let you go without talking about your book, This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism. Can you tell us a little bit about the book and the mission there?

Ashton Applewhite: Wow. That’s a big question. When I started on this path about 15 years ago I thought I had written one serious book before called Cutting Loose: Why Women Who End Their Marriages Do So Well.

Because guess what, I decided I had to in my marriage and it was quite analogous. I realised I had to end my marriage and I encountered the statistic that two thirds of divorces were initiated by women. And I was astonished. I thought it was 98% guys leaving their sad sack, old, withered, miserable, poor, broke wives behind for dashing trophy wives. And, that’s not the case.

And the catalyst for that book was why do so few people know these things? 22 years later investigating ageing, it was very much the same thing. It’s not that the things we fear about ageing are not real, It is that our fears are so out of proportion to the reality.

But writing the first book was really awful, so I thought I will just be a modern author/speaker/person, and I will tweet, and I will have a blog and I will post it. I will never have to write another damn book. But enough people said you have to write a book that I finally sat down and did it.

And then I could not get a publisher. I have tons of publishing experience, have been published by almost all the big houses at one time or another, the fancy house that had published the divorce book they had an option. I went and met with them, and the editor said, “we’re concerned that no one Is writing about this.” And my eyes did just what your eyes are doing, I think I managed to say tactfully, “I think you should see that as a feature, not a bug.”

Ash de Neef: I was trying to work out. Is that a problem?

Ashton Applewhite: Aren’t you in the new idea business? But no, most publishers are not in, you know, they’re conservative.

And so I ended up self publishing it with the help of my partner who has a lot of experience in publishing, thank God. Because he did a lot of back-end stuff really well. It’s a gorgeous book and I sold a bunch of copies, I did a Ted talk and that helped catalyse a public speaking career.

So I brought the damn box of books around to the things and signed them and sold them. And then a new division of McMillan called Celadon. Bought the rights two years ago. And now they’re carting the book boxes of books around and it’s slow. I mean, Culture change is slow.

I have sold, I just sold the Chinese language rights in Taiwan. but not yet in mainland China, Turkey, Slovenia, Japan, but not yet Spanish or French or German, it will happen.

But it’s an Interesting sort of marker, not that I’m unbiased. Of the sort of meandering ways that, the image I have in mind is how sort of rain water filters through the surface of the earth down to the groundwater. Of how ideas percolate into the mainstream.

Ash de Neef: Fantastic. And just so people can know exactly where they can find it, can you give us a link here? Where can people get, their hands on the book?

Ashton Applewhite: Just Google, This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism. You can of course get, it from Amazon, but I’ll give you a link. If you buy it from Celadon books, they will show you also, or on my website thischairrocks.com.

You will also have the option to purchase it from independent booksellers, which we should all support.

Ash de Neef: Awesome. Thank you so much for your time today Ashton.

Ashton Applewhite: You’re welcome.